Thirty-hour action for Vietnam

Overcoming nervous moments, Olivier Parriaux and Bernard Bachelard climbed close to the top of the Notre Dame Cathedral. Bernard Bachelard was tasked with planting the flag at the foot of the cross atop the cathedral spire. In the quiet night, there was a feeling that the “pop” sound from the unfurled flag was so loud that it could be heard on the ground. Both later sawed off all the iron bars that formed the steps to climb to the top of the tower to avoid others from removing the flag quickly. Then they used the rope brought with them to descend more easily. When they left the cathedral, the clock read 1:30 a.m.

|

|

|

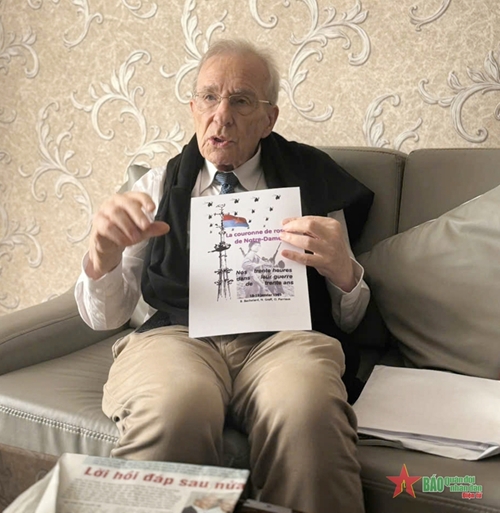

Olivier Parriaux introduces the drawing featuring the flag of the National Front for the Liberation of the South atop the Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris. |

They promptly got in the car and drove to Le Monde’s headquarters at 5 Italiens Street at 2 a.m. In the book “Le Vietcong au sommet de Notre-Dame,” they described that they were stuck in the middle of a large intersection since after the May 68 event, police set up barricades there. They were signaled to stop the car. Having looked at their dusty faces with surprise and the license plate, the policeman smiled brightly and let them go. “At that time, sweat poured out and soaked our clothes,” one recalled in the book.

Putting the envelope in the newspaper’s mailbox, the youngsters safely drove back to Lausanne that afternoon. Worrying about the fate of the flag and the possible consequences of the event, they rushed to Cenéac where hot news in the world was provided. They breathed a sigh of relief when learning that the flag was still fluttering on the cathedral spire.

In Paris, the flag-raising on January 19, 1969 morning became a special event. Paris Police Department sent firefighters to remove the flag, but they failed. On the ground, Parisians rushed out to look while reporters filmed and took photos. It was not until the afternoon that the flag was taken down. On January 20, 1969, U.S. President Richard Nixon was sworn in. On the front page of The New York Times and many other newspapers was the image of the flag of the National Front for the Liberation of the South fluttering atop the iconic historical architectural structure of Paris.

Answering a query of an U.S. reporter, a French police officer said that it was not an easy task for anyone to plant the flag which was clearly visible from the police headquarters, 250 meters away. The firemen tried to take it down but failed. He stressed that whoever did it must have been very brave.

In its January 20, 1969 issue, Le Monde published part of the press release of the unknown author about the purpose of the flag-raising and the protest announcement of the Saigon government accusing the incident of violating the beliefs of a sacred religious relic. The French newspaper also published the response of the Archbishop of Paris, stating that the material management of the cathedral belonged to the Paris government while the management of beliefs and spirit was the responsibility of the diocese; thus, the flag-raising event absolutely did not affect religious beliefs.

For U.S. progressive people, the flag-raising became a source of encouragement because it meant that they were not alone in the anti-war-in-Vietnam struggle.

|

|

|

Olivier Parriaux and Mr. Bernard Bachelard (right) talk to the PAN’s reporter. |

Decision to publicize identities

“Why have we remained silent for more than half a century, not identifying ourselves? It is because we considered it an iconic act and it achieved its set purpose. It does not matter who did it, the matter is that the flag was there as a testament to international solidarity, strong support of people in the world for the just struggle of the Vietnamese people,” said Olivier Parriaux.

However, another incident that urged them to reveal their story.

In an exclusive interview given to the People’s Army Newspaper (PAN)’s reporters at Central Palace Hotel in District 1, Ho Chi Minh City, near the Independence Palace, Olivier Parriaux recalled that it was the fire at the cathedral on April 15, 2019. Heartbroken by the fire, they reviewed everything associated with the nearly 800-year history of the heritage site and agreed that the flag-raising should be recognized as an integral part of the history of the cathedral.

Another special reason was that ten days after the fire, the PAN ran an article on the cathedral with a note on the flag fluttering on its spire. Olivier Parriaux accidentally read it after his Vietnamese French friends introduced it to him. The article surprised him. He never thought that a newspaper specializing in politics and military affairs had articles conveying human knowledge, expressing interest and sharp understanding and interpretation of art, architecture, culture, history, and world heritage sites. That showed a rich and knowledgeable cultural and spiritual life of both the newspaper and its readers. The article mentioned the flag as a confirmation of the connection with part of Vietnam's revolution.

Olivier Parriaux said that they were not heroes, but normal people having ideals to pursue, aspiration for peace for people in the world. Their decision of publicizing their identities was not for honor, gratitude, nor personal gain. When young, via newspapers, they saw the pains and catastrophic destruction that the U.S.-waged war brought to Vietnam and its people. The images of the fight and resilience of the Vietnamese people touched the hearts of millions of peace-lovers worldwide. “For those reasons, people in countries raised high the flag of struggle to support peace and independence for Vietnam,” he stressed.

The Swiss man shared that this was his first visit to the beautiful country of Vietnam, and he felt a warm and friendly welcome from Vietnamese friends. He visited Cu Chi Tunnel, a center for people with disabilities and orphaned children, and War Remnants Museum. What they eye-witnessed there helped them be aware of serious consequences of the war, though it was over many years ago. He said that they wanted to call on the community to join hands to support victims of Agent Orange/Dioxin to overcome difficulties and stabilize their lives. They are willing to stand side-by-side with Vietnam in the struggle for justice for Agent Orange victims in Vietnam and the world.

With red eyes, Bernard Bachelard said in a trembling voice that 20 years ago, he visited Ho Chi Minh City, Bien Hoa Airport and some historical sites and also the Dien Bien Phu battlefield relic site and he understood why Vietnam defeated both the French colonialists and the U.S. imperialists.

(to be continued)

By Phuong Thao - Linh Oanh

Translated by Mai Huong