The exhibition is expected to become a major attraction in the final months of 2025 as it interweaves three elements within one space: history, cuisine, and tourism.

Tracing memories through taste

Upon entering, visitors are immediately drawn to a humble meal with rice balls, boiled cassava, dried fish simmered in caramel sauce, and a few wild vegetables. This simple food recreates the daily meals of soldiers and civilians in Southern Vietnam during the resistance war.

|

|

|

Visitors enjoy sampling the dishes prepared by Old Pham Thi Oi. |

The exhibition is designed as an interactive curatorial experiment, inviting the community to co-create and retell the story of how meals became “silent soldiers,” sustaining life, fueling the will to fight, and nurturing solidarity between troops and people through years of hardship.

Exhibits are presented under various themes: family meals and wartime rations; food and survival during long marches; supply runs from the rear to the front; a recreation of the Hoang Cam stove (smokeless stove) widely used during the Dien Bien Phu Campaign; the “three no's” principle of Truong Son soldiers: no tracks, no smoke, no sound; and the improvised survival dishes of prisoners of war in Con Dao Prison.

Among the crowd, the rhythmic sound of a stone mortar grinding rice into flour echoes through the hall, evoking rural memories. Foreign visitors eagerly tried their hand at grinding rice, struggling to turn the heavy stone before laughing as grains were crushed into fine white powder.

“I now understand why each meal during wartime was so precious,” said Henry Mark, a visitor from the U.K. “To prepare meals for the soldiers, Vietnamese people had to work hard in extreme scarcity. Those meals were not just food, but symbols of solidarity and an unyielding will to live amid the horrors of war,” he added.

Nearby, bursts of laughter mixed with surprise as jars of southern fermented fish sauces were opened. While the pungent aroma initially startled foreign guests, curiosity soon compelled them to sample the strong flavors. For Southerners, these familiar tastes now serve as cultural bridges, reminding visitors that war was not only about smoke and gunfire, but also about modest meals and jars of fish sauce that nourished communities both physically and spiritually.

|

|

|

Visitors engage in interactive experiences. |

A highlight of the exhibition is the participation of 76-year-old Pham Thi Oi, who began cooking for soldiers at the age of 18. She personally prepared more than 40 banh tet (cylindrical sticky rice cake) and various rustic dishes for display.

“In the old days, we only wished for enough rice and cassava to fill soldiers’ stomachs,” she recalled. “Looking back, those meals were weapons, not only feeding the body but also sustaining the will to fight. I hope visitors, especially young people, will understand the value of every grain of rice and every banh tet.”

Oi’s presence and other stories transformed the exhibition into more than a showcase of exhibits. It became a “memory kitchen,” where flavors were inseparable from the spirit of resistance.

Promoting tourism through stories of history

The War Remnants Museum has long been one of Ho Chi Minh City’s most visited destinations. Over the past 50 years, it has welcomed more than 25 million visitors. In 2024 alone, the museum received 1.3 million visitors, over 80% of them from foreign countries.

During the recent April 30 holiday, nearly 19,000 visitors came, including more than 9,000 foreigners, cementing the museum’s reputation as a “bright star” on Vietnam’s cultural tourism map.

This exhibition adds even more appeal. Rather than simply observing objects or photographs, visitors are invited to taste, smell, and touch history.

|

|

|

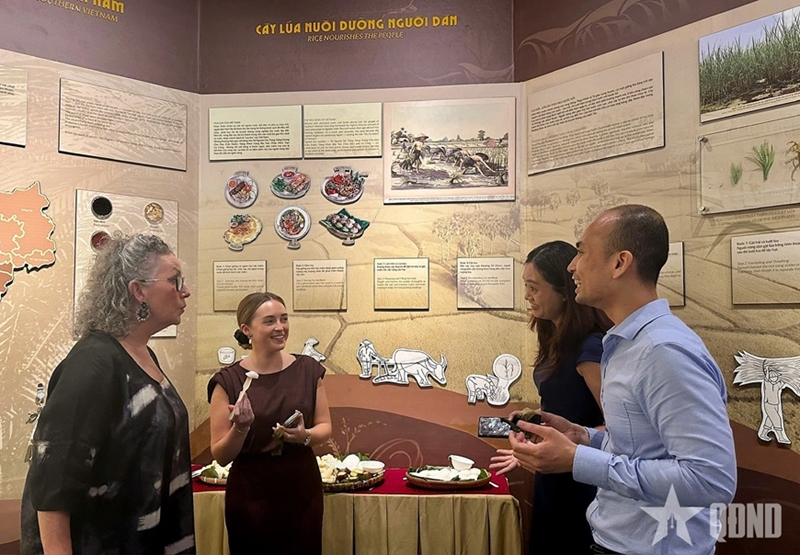

The exhibition attracts both domestic and international visitors. |

“I’ve read many books about the war in Vietnam. But today, for the first time, I could feel it through my senses of smell and taste. The scent of fish sauce, the smoke from cooking fires, these made me realize that wartime memories live not only in photos but in every simple meal,” said Claura Frern from Canada, moved by the experience.

Cuisine has enabled Vietnam to tell its history in a fresh yet intimate way, touching the hearts of visitors. Through these experiences, international guests gain a deeper understanding of the spiritual strength that carried the nation through war and of the compassionate Vietnam they encounter today.

In every grain of rice, every jar of fish sauce, and every roll of banh tet lies a story of resilience. Today, these once-humble flavors have become a “message of peace” to the world, contributing to the lasting charm of Vietnam’s most dynamic city. As Ho Chi Minh City surges forward, it needs distinctive cultural tourism products to keep visitors engaged. This exhibition is clear proof that when history is told through flavors, memories come alive, and tourism gains profound human value.

Translated by Chung Anh